(photo attributed to Wikipedia)

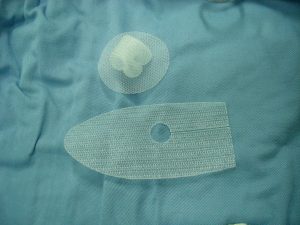

The Boston Scientific Corporation manufactured a transvaginal mesh prescription medical device that was designed to prevent the pelvic organs from falling through the vagina. The mesh sheet is made from a type of plastic and is implanted surgically into the patient. The plaintiff, Amal Eghnayem, had the sheet implanted in February of 2008 to treat her pelvic organ prolapse, but began to experience severe negative reactions in the following months. Amal experienced bleeding and pain during intercourse, incontinence and pelvic pain and pressure, and during an examination it was revealed that she had exposed mesh that was causing her severe symptoms. After an unsuccessful attempt to alleviate her pain, Amal visited a second doctor who found another mesh exposure and performed a second mesh-removal surgery. Following the second surgery, Amal’s pain subsided but by that time she had lost vaginal sensitivity. Amal subsequently filed suit seeking compensatory and punitive damages based on claims for negligent design defect, negligent failure to warn, strict-liability design defect and strict-liability failure to warn. Additionally, three other plaintiffs filed lawsuits and the United States District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia consolidated the suits.

At trial, the jury found for each of the plaintiffs on all four claims and awarded more than six million dollars to each plaintiff. The Boston Scientific Corporation appealed from the judgment on two separate grounds. First, the Boston Scientific Corporation argued that the district court abused its discretion by consolidating the plaintiff’s four suits and trying them together. Second, the Corporation argued that the district court abused its discretion by excluding all evidence relating to the Food and Drug administration’s clearance of the mesh for sale through the FDA’s “substantial equivalence” process. The trial court excluded the evidence under two different Federal Rules of Evidence. The first, Rule 402, provides that irrelevant evidence is not admissible, and the second, Rule 403, provides that relevant evidence may be excluded, “if its probative value is substantially outweighed by a danger of . . . unfair prejudice, confusing the issues, misleading the jury, undue delay, or wasting time.”

Atlanta Personal Injury Lawyer Blog

Atlanta Personal Injury Lawyer Blog